The Conservatives have a problem with young voters. In the 2017 election, only 27% of adults aged 18-34 voted for the Conservatives, in comparison to 62% of the 18-24 age bracket, and 56% of the 25-34 age bracket that voted for Labour. Yet, it is important to note that while the Conservative Party’s lack of appeal to younger adults has taken the appearance of an immutable law of physics, in 1983 the Conservatives were able to win over 41% of such voters.

Political divisions by age reflect growing social divisions – on attitudes and experiences – by age. It has been argued that today’s ‘millennials’ (the generation enjoying their childhood and adolescence at the turn of the century) are a “jilted generation”, locked out of the housing market, enduring insecure and low-paid employment, and facing record levels of debt thanks in part to rising tuition fees.

The challenges faced by young adults are not simply economic, but cultural and political too. There is evidence that suggests mental health problems, particularly depression and anxiety, are rising. Young adults are also experiencing a more polarised and turbulent political environment.

Of course, young adults also enjoy unparalleled opportunities, especially with regards to travel and leisure. They also currently enjoy record levels of employment, educational attainment and entrepreneurialism.

To examine these issues in more detail, we have conducted, in partnership with Opinium, public polling providing a snapshot of the attitudes of young adults towards public policy, political outlook, the Conservative Party and the state of Britain. We have released these results on the eve of our flagship Fixing the future conference.

Methodology

Polling was undertaken by Opinium and conducted between 3th and 5th July 2019. It consisted of one nationally representative sample of 2,002 UK adults. From this overall sample we produced a subset of 562 young adults (adults aged between 18 and 34), which we utilise to discuss the attitudes of young adults. The sample was weighted in terms of age, gender, region, employment status and social grade to reflect a nationally representative audience.

Throughout this analysis, the responses of young adults are compared to those of all adults. All adults includes young adults.

- Policy priorities

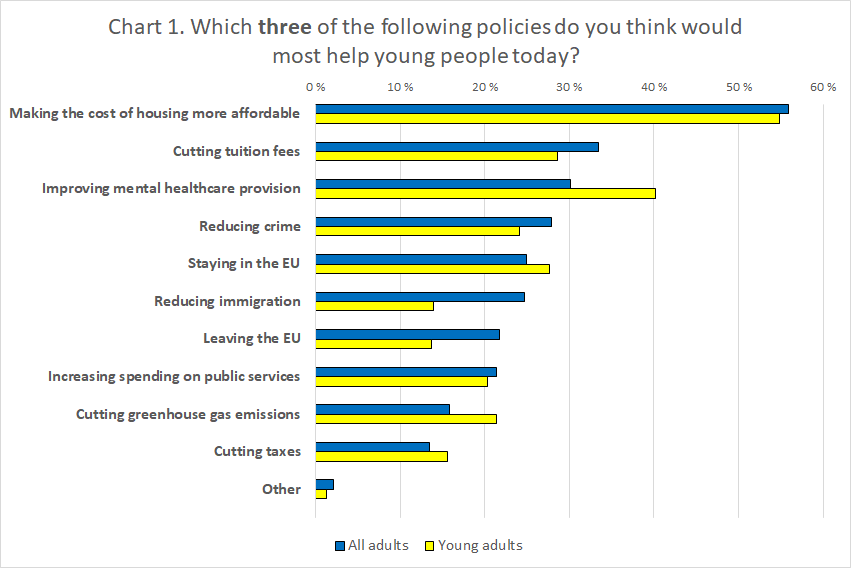

As can be seen in Chart 1, when asked to pick the top three policies which would help young adults the most, making the cost of housing more affordable emerged as the top choice among both young adults (55%) and all adults (56%), running significantly ahead of all other policies. A majority of young adults and all adults believe that making the cost of housing more affordable would help young adults the most.

The second favoured option among young adults (improving mental healthcare provision) was different to that chosen by all adults (cutting tuition fees). Young adults were more likely to think that improving mental healthcare provision would be among the most helpful (40%), in contrast to 30% of all adults. Young adults were also less likely to think that reducing immigration and leaving the EU (both at 14%) would help them in comparison to all adults (25% and 22% respectively).

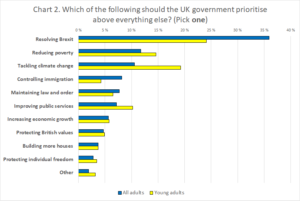

However, when asked what should the UK government prioritise above everything else in broader terms, a very different picture emerges. Resolving Brexit is seen as the top priority by all adults (36%) and young adults (24%), as can be seen in Chart 2 below. However, these results also suggest that young adults are not as concerned with Brexit to the same extent as all adults.

The gap in attitudes between young adults and all adults is most notable with tackling climate change, where 19% of young adults see it as the main priority for the UK Government, the second preferred option. This is in contrast with 11% of all adults.

2. Perceptions of Britain

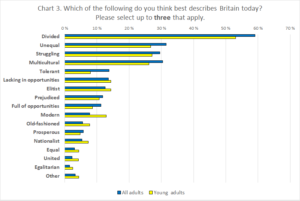

Young adults are broadly in agreement with all adults about what best describes Britain today, with ‘divided’ coming significantly ahead of all other options. This is illustrated in Chart 3 below.

Sadly, young adults today are somewhat gloomy about the state of Britain. ‘Unequal’ (27%) and ‘struggling’ (27%) emerged as the next two picks for young adults, which are also the same ordering as for all adults.

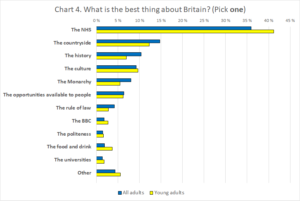

Young adults are broadly in agreement with all adults on what is the best thing about Britain, where the NHS is chosen, as seen in Chart 4 below. Notably, young adults are slightly more likely to see the NHS as the best thing (41% of young adults, in contrast to 36% of all adults). For young adults, this is followed by British countryside and British culture.

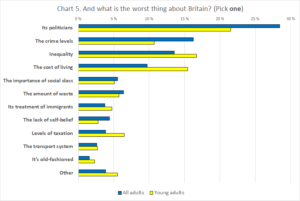

Chart 5 below illustrates that all adults (28%) and young adults (22%) have politicians at the top as the worst thing about Britain. Nonetheless, young adults are less likely than all adults to believe the worst thing about Britain is the crime levels (11%, as opposed to 16% of all adults), and are more likely to believe the worst thing about Britain is inequality (17%, as opposed to 14%) and the cost of living (15%, as opposed to 10%).

3. Perceptions of the Conservative Party

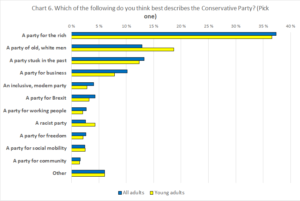

The dominant perception of the Conservative Party amidst both all adults and young adults (37%) is being a party for the rich, as can be seen in Chart 6 below. This is followed by descriptions of it as a ‘a party of old, white men’ (19%) and a ‘party stuck in the past’ (12%) by young adults, the same ordering as for all adults.

4. Political outlook

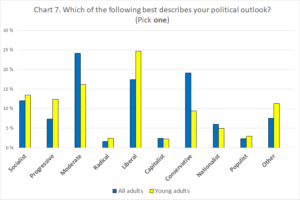

As Chart 7 below signifies, when asked to describe their political outlook, young adults are most likely to describes themselves as liberal (25%). The second most likely choice is progressive (12%). In comparison, only 17% of all adults would describe themselves as liberal and even less (7%) as progressive.

For all adults, they are more likely to describe their political outlook as moderate (24%). In contrast, 16% of young adults would describes themselves as moderate.

The difference is even starker for those who describe themselves as conservative, with only 9% of young adults choosing it, in contrast to 19% of all adults.

Conclusion

Our polling has provided a snapshot of the attitudes of young adults to public policy, politics and the state of Britain.

Our polling shows that young adults have a notably different political outlook, being much more likely to describe themselves as liberal and less likely as conservative. However, despite these differences there are also many commonalities. Young adults, like all adults, think that the best policy to help young adults today is to make the cost of housing more affordable.

There is common pessimism about the state of the country, with a shared view that Britain is, first and foremost, divided. As with all adults, they are also most likely to believe that politicians are the worst thing about this country.

Young adults are a generation that are most likely to regard themselves as liberal and believe that the best thing about Britain is the NHS. The Conservative Party has a long way to go in appealing to young adults and ridding itself of a common perception that it is a party for the rich.

Anvar Sarygulov is a researcher at Bright Blue

Notes

The full data tables for the polling can be found here.

We are grateful to Opinium for advising on and carrying out the survey.