The COVID-19 pandemic has generated a profound health and economic crisis in the UK.

More than nine million workers have been furloughed through the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS) for at least some time in the last three months, with the government paying 80% of their wages. Alongside this, there has been a raft of other grants, loans and funds available to businesses of all sizes to keep them afloat.

But economic recovery is likely to be a long and bumpy road. Businesses are likely to be negatively affected for some time by efforts to contain the pandemic and weak consumer demand.

Government currently plans to scale down CJRS over the coming months, and to end it fully by the end of October 2020. This will force businesses to make difficult decisions about their workforce.

We have partnered with Opinium to examine the experiences and expectations of businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, we want to provide helpful insight into how businesses have operated and will operate after the pandemic.

Methodology

Polling was undertaken by Opinium and conducted between 18th and 24th June 2020. It consisted of a balanced sample of 520 business leaders in the UK across different sizes and sectors. To ensure robust sample sizes, quotas of at least 100 were applied to each business size; sole-traders, micro, small, medium, and large businesses.

Questions related to furlough were only asked of businesses which have furloughed at least some of their stuff through the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS). Out of our sample, 297 businesses have utilised the scheme.

In regards to business size, ‘micro’ refers to a business with one to nine employees, ‘small’ to those with 10 to 49 employees, ‘medium’ to those with 50 to 249 employees, and ‘large’ to those with more than 250 employees.

- Furlough

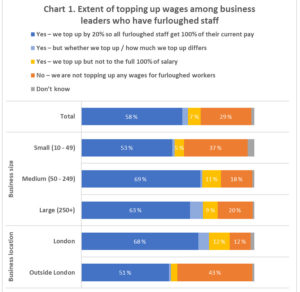

As seen in Chart 1 below, out of businesses which have utilised the furlough scheme, a majority (58%) have been topping up wages so that workers receive 100% of their current pay. In contrast, a significant minority (29%) have not been topping up wages at all. Importantly, of all business using the furlough scheme, 69% have topped up wages at least partly.

Medium (81%) and large businesses (79%) were far more likely to report topping up wages at least partly in comparison to small (59%) businesses. Although it should be noted that a majority of all types of businesses using the furlough scheme have topped up wages at least partly.

Similarly, London-based businesses were significantly more likely to be topping up wages (86%) at least partly than businesses outside of London (55%). But, again, across the country, most businesses using the furlough scheme have topped up wages at least partly.

Base: 297 UK business leaders. Results for sole trader and micro business sizes are not shown due to small subsample size.

Base: 297 UK business leaders. Results for sole trader and micro business sizes are not shown due to small subsample size.

From August, the Government expects businesses using the furlough scheme to start paying, gradually, a greater share of wages and pensions contributions for furloughed employees.

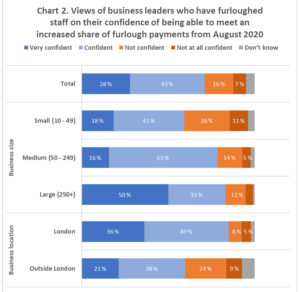

As seen in Chart 2 below, most businesses (71%) are confident or very confident that they will be able to pay an increased share of wages for furloughed employees.

However a notable minority of businesses are not or not at all confident (24%) that they will be able to meet an increasing part of the wages for furloughed employees, indicating that a sizeable number of businesses are likely to struggle with the gradual withdrawal of the CJRS.

Once again, medium (78%) and large (83%) businesses – and businesses operating in London (85%) – are more likely to express confidence that they can pay in increasing part the wages of furloughed employees in comparison to small businesses (59%) and those based outside of London (60%). Although, it should be highlighted that a majority of businesses of all sizes and across the UK are confident they will be able to pay an increasing share of the wages of furloughed employees.

Base: 297 UK business leaders. Results for sole trader and micro business sizes are not shown due to small subsample size.

Unemployment has been rising since Covid-19 came to the UK. But, with the withdrawal of the CJRS, there are fears of mass unemployment.

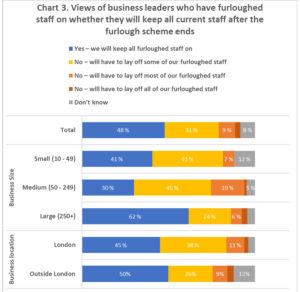

As seen in Chart 3 below, just under half of businesses (48%) expect to keep all furloughed staff on the payroll after CRJS ends. However, a considerable proportion (44%) of businesses do not expect to keep all of their current staff on payroll after the CJRS ends, with 31% of businesses expecting to lay off some furloughed staff, 9% expecting to lay off most of furloughed staff and 3% expecting to lay off all of furloughed staff.

There is significant contrast between medium and large businesses. Most large businesses (62%) are expecting to keep all of their furloughed staff on the payroll after the CJRS ends, while most medium businesses (65%) are expecting to lay off at least some people who are currently furloughed. The picture is more mixed for small businesses, with 47% expecting to lay off at least some furloughed staff, and 41% expecting to keep all of them.

Businesses in London are more likely to expect at least some lay offs of those who are currently furloughed (51%) than businesses outside of London (38%).

Base: 297 UK business leaders. Results for sole trader and micro business sizes are not shown due to small subsample size.

2. Operating during a pandemic

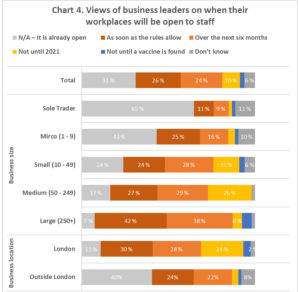

As seen in Chart 4 below, 31% of businesses have already opened up, or have stayed opened up, to staff to work from. Meanwhile, most businesses are planning to open their workplaces to staff to work from as soon as the rules allow (26%) or over the next six months (24%). Only a small number of businesses currently expect not to open to staff until 2021 (10%) or until a vaccine is found (3%).

While a majority of sole traders (65%) and a significant number of micro businesses (43%) are already open, the numbers are notably lower for small (24%), medium (17%) and large (7%) businesses.

Notably, businesses in London are far less likely to already be open (11%) compared to businesses elsewhere in the UK (40%). London businesses and are far more likely to expect to stay closed until 2021 (24% in comparison to 4% of non-London businesses).

Base: 520 UK business leaders

The Government has continued to relax social distancing rules as COVID-19 caseload has fallen. From July 4th 2020, most businesses will be able to reopen, provided they follow government guidelines on how to protect their employees and customers. Furthermore, the Government has relaxed the two metre rule to one metre where two metre distance is not viable, as long as other risk mitigation is implemented.

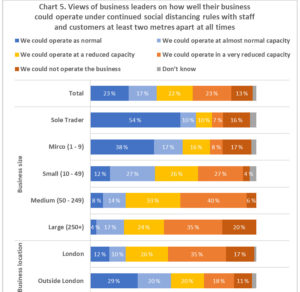

As seen in Chart 5 below, the vast majority of businesses (85%) report that they could operate to some extent under continued social distancing rules where staff and customers are at least two metres apart. But only 23% of businesses could operate as normal. In contrast, 13% would not be able to operate at all. This suggests that the recent change in policy from two metres to one metre could be of significant help to a large number of businesses.

Sole traders (54%) and micro businesses (38%) are far more likely to be able to operate as normal even under stringent social distancing rules in comparison to small, medium and large businesses (12%, 8% and 4% respectively), with the majority requiring many or some adjustments while operating under a reduced capacity.

Businesses outside London are more likely to be able to operate as normal (29%) compared to those in London (12%). In contrast, a majority of businesses in London could either not operate at all (17%) or only in a very reduced capacity (35%) under stringent social distancing, whereas outside London this falls to 11% and 18% respectively.

Base: 520 UK business leaders.

3. Operating during a pandemic

Will businesses ever return to normal? We tested initial attitudes of business leaders.

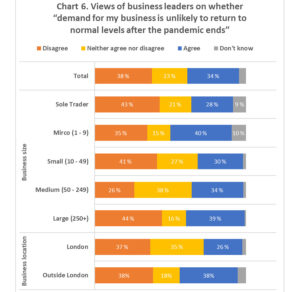

As seen in Chart 6 below, when asked about whether demand is unlikely to return to normal levels after the pandemic ends, 34% agreed, 38% disagreed, 23% neither agreed or disagreed, and 5% said they didn’t know. This indicates there is a lot of uncertainty about demand for business in the long-term, even after the pandemic.

There are some minor variations on expectations of demand among businesses of different size. More notably, business leaders outside of London are more likely to have expectations that demand is unlikely to return to normal levels after the pandemic ends (38%) in comparison to London businesses (26%).

Base: 520 UK business leaders.

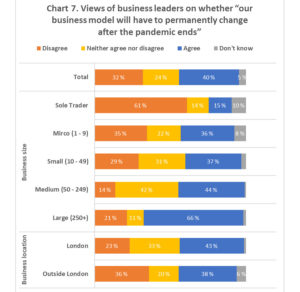

As seen in Chart 7 below, a significant number of business leaders (40%) agree that their business model will have to permanently change after the pandemic ends, while 32% disagreed. This means businesses are more likely to report than not that their business model will have to change permanently.

However, the majority of sole traders (61%) disagreed that their business model will change, while a majority of large businesses agreed (66%). Views among businesses of other sizes were more mixed, with micro and small businesses being more likely to disagree (35% and 29% respectively) compared to medium businesses (14%), as the latter was more likely to not hold an opinion in either direction.

While similar number of business leaders in London and outside of it agreed that business models will have to change (43% and 38% respectively), levels of disagreement were notably lower in London (23%) compared to outside of it (36%).

Base: 520 UK business leaders.

Conclusion

The Government’s furlough scheme is generous relative to support offered in other countries. Most businesses using it are managing to top-up the wages of their furloughed staff and expect to do so in the future as the conditions around using CJRS change.

But a significant number of businesses lacks confidence in paying more wages for their furloughed staff and expect to let go at least some furloughed employees. A significant increase in unemployment is highly likely.

The social distancing measures have helped to stop the pandemic from running out of control, and businesses will benefit from the recent relaxations in the two-metre rule. But the threat of a resurgence continues to trouble businesses, with business leaders more likely to believe that demand for their trade will not return to normal for some time and that their business model is likely to be permanently changed.

The Government has already implemented extraordinary measures to address the COVID-19 pandemic. In the months ahead, they will have to effectively follow-up on current policies, to both contain the economic fallout from the crisis and to build the road to the recovery.

Anvar Sarygulov is a senior researcher at Bright Blue

Notes:

The full data tables for the polling can be found here.

We are grateful to Opinium for advising on and carrying out the survey.