Introduction

The severe flooding of last November and December, as well as recent Storms Ciara and Dennis, have brought renewed focus on whether the Government is doing enough to protect and support high flood risk communities, both before and after flood events. For some hard hit places, for example in the Doncaster area, it has been the second or third major flood event they have experienced in two decades.

The UK needs to become a climate ready nation. We know that flooding is going to get worse with climate change. This means not only that we develop foresight on physical impacts and effective adaptation policies at a technical level, but also that we understand the human impact. Supporting flood-hit communities, rather than leaving them to shoulder crippling financial impacts alone, is a clear test of whether we can respond to climate change as a decent society.

This needs to be viewed not just as a matter of individual tough luck. It is all too easy to foresee scenarios where high-risk communities experience repeat flooding, the flood component of home insurance becomes prohibitively expensive or unavailable for growing numbers of properties, and this has knock-on effects for the entire community and local economy. These impacts could include small businesses being deterred by lack of insurance cover; the cost of uninsured losses hitting spending power on local goods and services; and rows of blighted houses which cannot be mortgaged or sold on —what one commentator has called “flood ghettos” [i].

Government policy

There are major concerns over the cost and availability of flood insurance; the effectiveness of defences and land management; and, what can feel to some householders like arbitrary rules on who is entitled to flood recovery grants, financial support provided by government to households, businesses and communities affected by flooding [ii]. Indeed, shortly after the late 2019 floods, the then Environment Secretary announced a review of flood insurance to investigate why some at-risk householders are still apparently unable to insure their homes despite the existence of a government and industry scheme (Flood Re) designed to help them.

Admittedly, policymakers recognised concerns over flood insurance many years ago. Flood Re was set up by the Government and the insurance industry to make flood insurance affordable for households in high risk areas, and has been running since 2016. Insurers can pass the flood risk element of household insurance to Flood Re for a fixed price, lowering household premiums and excesses. Some insurers directly pass the cost of the scheme onto all policyholders, and at its instigation it was estimated that the cost to an individual policyholder would be equivalent to an increase of £10.50 per policy [iii]. The scheme is due to be phased out in 2039 at which time all flood insurance will be ‘risk-reflective’.

Any scheme which spreads risk from those who can do most to reduce it to other parties inevitably raises the issue of moral hazard – the idea that transferring the cost of risky behaviour reduces the incentive to avoid it. To tackle moral hazard, Flood Re was limited to only covering properties built before 1st January 2009 (referred to below as ‘post-2008 properties’).

Disincentives to increase flood risk are a good public policy goal. However, in their 2019 progress report on UK climate adaptation, the Committee on Climate Change said: “We have no evidence (and are aware of none being collected) to indicate that this [2009 cut-off point] has influenced where developers try to locate new developments” [iv]. This raises questions over whether it is actually affecting behaviour.

There is no legal requirement to provide flood risk information to homebuyers, although the Law Society publishes guidance on good practice in informing clients of flood risk during conveyancing.

We should consider that the 2009 cut-off, rather than reducing exposure, may have simply left unwary homebuyers, to use an inappropriate expression, ‘high and dry’. As they are not covered by Flood Re, concentrations of post-2008 properties in high flood risk areas, such as new estates, are naturally some of the most vulnerable in the country to becoming ‘insurance blackspots’.

It is worth assessing how widespread this problem might be, and which parts of the country might be most affected.

Identifying ‘at-risk’ properties

The number and locations of post-2008 properties in areas at risk of flooding in England can be estimated using Land Registry data on property transactions alongside Environment Agency geospatial flood risk data products.

As Land Registry data provides the postcode of each transaction, and states whether properties are new builds, it can be estimated how many post-2008 properties have been constructed in various flood zones in each postcode and local authority district. See the Annex for more detail on the methodology for this data analysis.

The scope of the data analysis is:

- England only (due to time constraints, given that UK flood maps are compiled by four different agencies, and property transaction data by three)

- Residential (not commercial) properties

- Risk of flooding from rivers and the sea only, not from surface water, groundwater or reservoirs

First, it’s helpful to summarise the various flood risk categories the Environment Agency, government and local authorities use. These are illustrated in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Categories of flood risk used in planning policy and public information

| Flood risk zone or category |

Definition |

Takes defences into account? |

Examined in this analysis |

| Flood Map for Planning Risk[v] zones |

| Flood Zone 1 |

less than 0.1% annual probability of river or sea flooding |

No |

No |

| Flood Zone 2 |

0.1-1% annual probability of river flooding OR

0.1-0.5% annual probability of sea flooding |

No |

| Flood Zone 3 |

greater than 1% annual probability of river flooding OR

greater than 0.5% annual probability of sea flooding |

Yes |

| Flood Zone 3, benefitting from defences |

As above, but benefitting from defences |

Presence, yes; probability, no |

Used to identify properties in Zone 3 not benefitting from defences |

| Long term flood risk information[vi] categories |

| Very low risk |

less than 0.1% annual probability of river or sea flooding |

Yes, probability calculation takes defences into account |

No |

| Low risk |

0.1-1% annual probability of river or sea flooding |

No |

| Medium risk |

1-3.33% annual probability of river or sea flooding |

No |

| High risk |

greater than 3.33% annual probability of river or sea flooding |

Yes |

Flood Zones 1, 2 and 3 are used in planning policy, and the probability of flooding described is the natural level in the absence of defences (i.e. unmitigated).

Planning policy defines land at risk of fluvial and coastal flooding to be mostly that in Zones 2 and 3.

In addition, four flood risk categories ranging from ‘very low’ to ‘high’ are used in the Long term flood risk information service, as detailed in the second part of Table 1. This is designed to inform householders of their flood risk, in terms of background (rather than imminent) and actual (rather than unmitigated) flood risk. Even in defended areas, flood defences “reduce but do not completely stop the chance of flooding as they can be overtopped, or fail” [vii].

For simplification, this analysis examines properties in just three categories of at-risk postcodes, defined here as follows:

- Category A: postcodes in Flood Zone 3, defended or undefended

- Category B: postcodes in Flood Zone 3 which are not in an area benefitting from defences

- Category C: postcodes where at least half of all residential properties are at high risk of flooding (>3.33% annual probability), regardless of defences

These categories are not mutually exclusive. Category A includes all the properties in Category B and the majority in Category C. Category C are the greatest at-risk properties.

Concentrations of at-risk post-2008 properties in England

Land Registry data suggests around 70,000 post-2008 residential properties are in Flood Zone 3 in England (Category A, as defined above), although compared to official Government statistics, this is an underestimate, as the Annex explains in further detail. These 70,000 properties are at risk of becoming uninsurable due to their ineligibility for Flood Re.

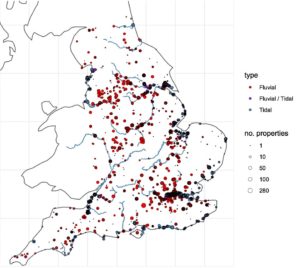

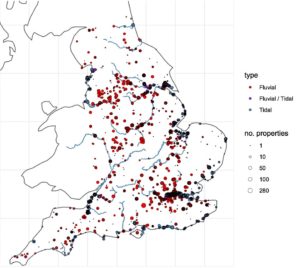

Figure 1 below shows the locations of these at-risk post-2008 residential properties, with each circle representing a postcode, and the size of the circle reflecting the number of properties (to a logarithmic scale).

Figure 1: Postcodes in England in Flood Zone 3 (Category A) with post-2008 residential properties not covered by Flood Re

As Figure 1 indicates, a majority (52%) of these at-risk properties are in Greater London; however, an overwhelming majority (93%) of these London properties are in areas benefitting from defences, in particular the Thames Barrier.

Other obvious clusters include Humberside and the Yorkshire part of the Humber river basin (the Rivers Aire, Ouse and Don), Somerset, Lincolnshire and Fens, Thames Estuary, the Trent and Soar in the Midlands, Mersey and Greater Manchester, and the Lancashire coast.

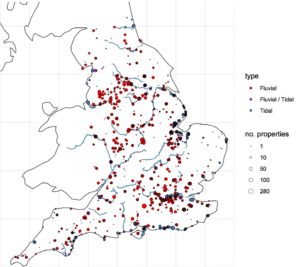

Perhaps a stronger indicator of vulnerability to becoming uninsurable is the number of post-2008 properties which have been built in undefended areas (Category B), estimated at around 20,000.

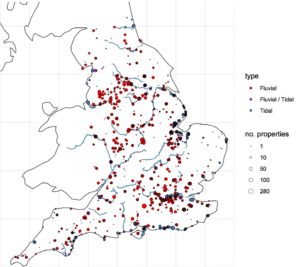

Figure 2 below repeats the map shown in Figure 1, but removes Flood Zone 3 postcodes which benefit from defences. Thus, it illustrates the location of Category B at-risk postcodes – those in Flood Zone 3 without defences.

Figure 2: Postcodes in England in Flood Zone 3 with post-2008 residential properties not covered by Flood Re and not benefitting from flood defences (Category B)

Much of London, Kingston upon Hull, Somerset and the Lancashire coast no longer show up strongly, but other clusters are left intact. Specifically, some of the greatest concentrations of at-risk post-2008 properties without defences include: Boston and Spalding in Lincolnshire; parts of central Leeds, Bristol, York, Shrewsbury and Chelmsford; Mexborough near Doncaster; the Leicester urban area; the Sussex coast; Tonbridge in Kent; King’s Lynn in Norfolk; and certain London boroughs with a risk of flooding from River Thames tributaries rather than the River Thames itself.

Four further points of interpretation of the analysis so far should be noted.

First, remember these locations are flagged as vulnerable not because their flood risk is necessarily higher than other undefended Zone 3 locations, but purely because of the concentration of properties ineligible for insurance via Flood Re, since a higher proportion of them were built after 2008. We call these areas potential ‘insurance blackspots.’

Second, flood risk can be highly postcode-specific and just because a town contains a few streets at risk of uninsurability, that does not mean the whole town is a potential insurance blackspot.

Third, remember we are not mapping which properties are currently uninsured or uninsurable, but flagging vulnerability to this eventuality, although it is possible some of the postcodes flagged may already be experiencing it.

Fourth, simply pinpointing the location of these properties does not say anything about how well local flood risk assessments or design have dealt with the risk.

Top 10 local authorities with the most at-risk properties

We can now illustrate the local authorities that have the most residential properties in each Category, by both number and property value.

By number of residential properties

Table 2 below presents the top ten local authority districts (LADs) with the greatest number of post-2008 properties in Flood Zone 3, both as a whole (Category A) and undefended (Category B), including and excluding London.

Table 2. Local authority districts with the greatest number of post-2008 properties in Flood Zone 3, both as a whole (A) and undefended (B), including and excluding London

| A: no. post-2008 residential properties in Flood Zone 3 |

B: no. post-2008 residential properties in Flood Zone 3, undefended |

| incl. London |

excl. London |

incl. London |

excl. London |

| local authority |

no. |

local authority |

no. |

local authority |

no. |

local authority |

no. |

| Tower Hamlets |

6761 |

Kingston upon Hull |

3212 |

South Holland |

1158 |

South Holland |

1158 |

| Southwark |

6286 |

North Somerset |

2064 |

Boston |

982 |

Boston |

982 |

| Wandsworth |

5314 |

Sedgemoor |

1759 |

Leeds |

616 |

Leeds |

616 |

| Newham |

4511 |

Dartford |

1205 |

Newham |

585 |

Bristol, City of |

443 |

| Greenwich |

3319 |

South Holland |

1158 |

Wandsworth |

469 |

Doncaster |

442 |

| Kingston upon Hull |

3212 |

Boston |

982 |

Bristol |

443 |

Tonbridge & Malling |

427 |

| Hammersmith & Fulham |

2451 |

Doncaster |

727 |

Doncaster |

442 |

East Lindsey |

322 |

| Lewisham |

2131 |

Thurrock |

659 |

Tonbridge & Malling |

427 |

York |

321 |

| North Somerset |

2064 |

Selby |

650 |

Greenwich |

339 |

Shropshire |

316 |

| Lambeth |

2039 |

Wyre |

645 |

Lewisham |

338 |

Chelmsford |

308 |

As expected, most of the Top 10 LADs for Zone 3 postcodes are in London. Elsewhere, Hull and Somerset predominate, but disappear when flood defences are taken into account (i.e. Category B).

Lincolnshire, containing Boston, South Holland and East Lindsey LADs, stands out as the county with the greatest concentrations of undefended post-2008 properties.

For simplicity, the results presented do not disaggregate by property type. However, it should be noted that the Land Registry data shows that a clear majority (70%) of the properties identified in Zone 3, and 55% of the undefended properties in Zone 3, are flats (the figures are 41% and 49% respectively excluding London).

It is important to note that contents insurance for rented or leasehold flats built before 1st January 2009 is covered by Flood Re (contingent on meeting other eligibility criteria), but otherwise properties in blocks of more than three residential flats are not eligible, regardless of their age.

Although flats on upper storeys do not suffer the same direct impacts of flooding as ground floor flats and houses, access and utilities can suffer and occupants may need to be accommodated elsewhere (covered by their insurer); and the building as a whole can be deemed uninhabitable. Tenants may have the cost of high flood insurance passed onto them via management charges, and many insurers do not take storey into account when calculating premiums. It would not be valid to assume, therefore, that uninsurability is not also a potential problem for the flat dwellers in these at-risk postcodes.

By property value

As Land Registry data includes house prices, we can also summarise the results of our analysis of at-risk properties, by property value.

Table 3 below lists the ten LADs with the greatest estimated value of post-2008 properties in Flood Zone 3, both as a whole (Category A) and undefended (Category B), including and excluding London.

Table 3. Local authority districts with the greatest value of post-2008 properties in Flood Zone 3, both as a whole (A) and undefended (B), including and excluding London

| A: value of post-2008 residential properties in Flood Zone 3 |

B: value of post-2008 residential properties in Flood Zone 3, undefended |

| incl. London |

excl. London |

incl. London |

excl. London |

| local authority |

£ million |

local authority |

£ million |

local authority |

£ million |

local authority |

£ million |

| Southwark |

4527 |

Kingston upon Hull |

472 |

Wandsworth |

262 |

South Holland |

173 |

| Wandsworth |

4255 |

North Somerset |

443 |

Newham |

215 |

Leeds |

173 |

| Tower Hamlets |

3411 |

Sedgemoor |

304 |

South Holland |

173 |

Boston |

151 |

| Hammersmith & Fulham |

2612 |

Dartford |

260 |

Leeds |

173 |

Tonbridge & Malling |

117 |

| Westminster |

2299 |

Windsor & Maidenhead |

177 |

Boston |

151 |

Bristol |

114 |

| Newham |

1722 |

South Holland |

173 |

Greenwich |

141 |

Windsor & Maidenhead |

84 |

| Lambeth |

1712 |

Leeds |

173 |

Tower Hamlets |

135 |

York |

80 |

| Greenwich |

1539 |

Thurrock |

159 |

Tonbridge & Malling |

117 |

East Hertfordshire |

73 |

| Lewisham |

804 |

Boston |

151 |

Bristol |

114 |

Brighton & Hove |

72 |

| Kingston upon Hull |

472 |

Tonbridge & Malling |

130 |

Lewisham |

93 |

Worthing |

70 |

Property prices are converted to 2015 equivalents using the UK House Price Index

This analysis suggests that, in total, about £31 billion worth of property has been built in Zone 3 after 2008, of which about £5 billion is undefended.

The results are similar to Table 2, with the promotion of London and south-eastern LADs up the rankings.

A large proportion of the total £31 billion figure refers to the parts of London protected by the Thames Barrier, as would be expected. However, there is also at least £700 million pounds worth of post-2008 property in Flood Zone 3 in Somerset (North Somerset and Sedgemoor); and hundreds of millions of pounds worth of property which is neither eligible for insurance via Flood Re nor protected by flood defences in parts of London, Lincolnshire and Yorkshire.

Greatest at-risk properties

There has been apparently very little new building in some of the greatest at-risk postcodes, defined earlier (Category C) as those areas where at least half of all residential properties have a 1-in-30 or higher annual chance of flooding, irrespective of defences. Land Registry data suggests there have been about 3,000 properties built in England in these postcodes since 2009.

Table 4 below shows the top five LADs for the greatest at-risk postcodes, by number and value of these properties.

Table 4. Local authority districts (LADs) with the greatest number and value of post-2008 properties in the greatest at-risk category of postcodes

| C: At least 50% of residential properties in postcode are at High risk (>3.33%) of flooding |

| no. post-2008 properties |

value of post-2008 properties |

| local authority |

no. |

local authority |

£ million |

| Lewisham |

297 |

Lewisham |

99 |

| Leeds |

261 |

Kingston upon Thames |

58 |

| Kingston upon Thames |

200 |

Leeds |

41 |

| Doncaster |

160 |

Windsor & Maidenhead |

34 |

| Canterbury |

141 |

Medway |

17 |

At this level we might be talking about only a few blocks of flats, or a couple of new housing estates.

Some particular clusters of note from Table 4 are the area near the confluence of the Rivers Quaggy and Ravensbourne in Lewisham; the outskirts of Mexborough near Doncaster; and an area near where the Stour branches in central Canterbury.

Future housebuilding

20,000, even 70,000, properties that are at-risk of not having flood insurance are not large numbers in terms of the current total UK housing stock. However, it is just as well to develop some foresight on this issue for certain specific locations, and in the light of current trends.

According to the Environment Agency, the number of properties in the flood plain is set to almost double over the next 50 years, if current planning outcomes continue [viii]. As a consequence, under its current rules, there will be growing numbers of at-risk properties which are not entitled to insurance via Flood Re.

It is worth highlighting what the National Planning Policy Framework states [ix]:

“Inappropriate development in areas at risk of flooding should be avoided by directing development away from areas at highest risk (whether existing or future). Where development is necessary in such areas, the development should be made safe for its lifetime without increasing flood risk elsewhere.”

A sequential test is applied to “steer new development to areas with the lowest risk of flooding”, and where this is not possible it must be demonstrated that “the development would provide wider sustainability benefits” which outweigh the flood risk. Developers are required to undertake a site-specific flood risk assessment in areas at risk of flooding when applying for planning permission, including how the site is likely to be affected by climate change.

Given the pressure local authorities are under to build houses and the land constraints they face, it is unrealistic to expect there will be no building in Zone 3 (Category A) areas. Therefore, homeowners of new properties need to be fully informed of their flood risk, and this should include giving them a heads up that their risk may increase with climate change and they may find it hard to get insurance.

While climate change may be taken into account in the planning process, this information is not readily accessible to householders, and it’s fair to say it would probably not occur to the vast majority of people to consider it.

The future of Floor Re

Flood Re has extended affordable flood insurance cover to many householders who would otherwise not have had it. However, the new government-commissioned Flood Insurance Review will no doubt spark a debate about whether everyone who could benefit from the Flood Re scheme is doing so.

The question of whether it is fair or effective (in public policy terms) to have set a retrospective cut-off date of 1st January 2009 is central to the debate. Indeed, the head of general insurance at the UK’s largest insurance company, Aviva, recently said that it should be extended to apply to homes built after this date, in conjunction with improved planning and resilience [x].

Concerns over moral hazard are valid. Given that policyholders are cross-subsidising risky households via Flood Re, it is important to keep the costs down for everyone and disincentivise poor development choices. It is also reasonable to assume that property owners should take on some degree of personal responsibility to understand and reduce their flood risk.

However, the cost of flood insurance can only be a disincentive for house-building if it in some way affects the developer’s bottom line.

Basic economic theory would assume a world of rational home-buyers perfectly informed about their flood risk, factoring potential future costs into the amount they are willing to pay for a house, and balancing these against the desirability of other features. In this world, they pay a lot less to developers for their flood-prone houses, creating a financial incentive for them to build somewhere else.

So much for the textbooks — are we really confident this is what has actually happened? A 2013 survey for the Environment Agency found that over half of people living in flood risk areas either don’t know or don’t accept their risk [xi].

Is it really the case that everything has been done to inform homebuyers of their flood risk? The Pitt Review of lessons learned from the 2007 floods recommended that flood risk should be part of mandatory search requirements during property purchase twelve years ago [xii]. This led to the inclusion of flood risk information in Home Information Packs, which were given to homebuyers and included a Property Information Questionnaire with details on flood risk – but this policy was discontinued in 2010. It would be the height of naivety to believe that homebuyers understand their flood risk in a changing climate — including potential uninsurability — when accessible public information isn’t yet available on future flood risk. This looks like a case of information failure.

A Government note on the flood risk information currently available to homebuyers, linked to the Water Act of 2014 (which established Flood Re) while in its Bill stage, stated [xiii]:

Surveys/investigations into flood risk are not required by law. It is a well-established principle of the conveyancing process that the onus is on the buyer of a property to conduct their own searches and investigations into the potential risks to that property.

In other words, caveat emptor, end of story. If policymakers are serious about helping ordinary members of the public deal with climate impacts then this needs to change.

Policy recommendations

Four specific policy recommendations are as follows:

The new Secretary of State for the Environment should continue with the Flood Insurance Review and, as part of it, consider a reset for the cut-off point for Flood Re eligibility.

There are at least two grounds for this: (i) the Government has not done enough to inform new-build homebuyers of their flood risk over the past decade; and (ii) there is no evidence the cut-off has succeeded in its policy aim of disincentivising development in at-risk areas.

A later cut-off point for eligibility should be determined in conjunction with a clear strategy to: (i) provide new and better information on flood risk (see below); (ii) ensure property-level resilience is being advanced (see below); and (iii) engage the public on this issue, and inform them of any responsibilities policymakers believe them to have.

Regarding the extra cost of extending the Flood Re scheme, having an estimate of the number of properties involved, similar to the one we have attempted in this analysis, would at least allow an informed discussion of the likely cost, and potential revenue sources to cover it.

Given the growing prominence of flooding, it should be considered that, if asked whether they would be willing to pay a little extra on their home insurance policies to help others, members of the public might well agree.

Introduce new mandatory Flood Performance Certificates (FPCs) for all homes being sold with information on property-level resilience, Flood Re eligibility, government advice on reacting to flooding, information on flood defences, and the impact of climate change on future flooding risk.

Failing this, sellers, conveyancing solicitors or landlords should be obliged to provide a recognised flood risk report (for example a Land Registry flood risk report) to all people purchasing properties.

Property purchase is an ideal moment to alert homebuyers to actions they can take to make their property more resilient.

The Social Market Foundation, in research for Flood Re, have previously suggested the introduction of “Flood Performance Certificates” (FPCs), analogous to Energy Performance Certificates, to summarise flood risk information for homebuyers [xiv]. They suggested FPCs could cover flood risk and history, any resilience measures that have been recommended by a surveyor, and an assessment of whether they have been taken up.

Building on this, these FPCs could also include: (i) eligibility for insurance via Flood Re, and where eligible, the fact that this will be withdrawn from 2039; (ii) government advice on how to react to flooding events; (iii) information on defences in their area; and (iv) a basic statement that their flood risk may increase due to climate change.

Ultimately, forward-looking flood risk information incorporating climate change and sea level rise should be provided. The Committee on Climate Change (CCC) note that there is currently no national map of future flood risk [iv]. If possible, the Environment Agency should be given appropriate support to expedite this.

Flood risk reports are available via the Land Registry at a cost of £10.80 including VAT, a negligible sum. Either sellers and landlords could be required to obtain this and give it buyers or tenants; or it could be required of conveyancers, passing the cost onto their client in their fees.

Reform the Building Regulations so by a set date all new-build properties in Zones 2 and 3 have property-level flood resilience (PFR) measures.

Reform the National Planning Policy Framework to strengthen importance of PFR measures.

Require all local authorities to monitor and report on the extent to which at-risk properties in their area have PFR measures.

Property-level flood resilience (PFR) refers to modifications to properties to enable them to incur lower damages and recover more quickly from flooding, such as flood protection barriers, raised electrics and tiled floors. Figures compiled by the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) indicate that the total number of properties which have installed property-level flood resilience measures are probably in the low thousands, with annual uptake estimated at 415 properties per year [iv]. The CCC point out this is a long way short of the rate required both to phase out Flood Re and “to adapt to even a 2ºC global temperature scenario”.

Flood Re consider uptake of flood resilience measures to be a core component of how the market can transition away from the scheme by 2039 [xv] and have called for premiums to take them into account [iii].

Defra has convened a Property Flood Resilience Roundtable which recently published a draft voluntary Code of Practice on PFR [xvi], and one of its Task Groups has been examining the role of building regulations [xvii].

While civil servants and industry stakeholders work on the technical aspects of such proposals, what is needed is for the Government to set some clearly signposted ambitious goals for developers, insurers and local authorities. For example, changing the Building Regulations so that by a reasonably near-term set date (before 2025) they will include PFR measures for properties in Zones 2 and 3. This could leverage the dialogue already taking place amongst knowledgeable stakeholders and give it a destination.

Furthermore, the National Planning Policy Framework could include stronger statements on PFR, and local authorities could be required to monitor and report on the extent to which at-risk properties in their area have PFR measures.

At a minimum there could be a public information campaign on PFR targeted at priority at-risk and recently flooded communities.

The Government should identify, map and monitor ‘flood risk hot spots’ – areas of the country particularly at risk of widespread and consequential impacts from flooding.

In the years ahead, there will be areas of the country that will be particularly at risk of widespread and consequential impacts from flooding.

These areas will not just be defined through physical risk, but through predisposition to social, economic, public safety, public order or even national security impacts. These severe impacts will be shaped by factors such as lack of insurance coverage, livelihoods vulnerable to flooding (such as farming), dependence on at-risk infrastructure, possible emergency response difficulties, likely ineligibility for flood defences and social vulnerability. For example, given the importance of Lincolnshire and the Fens in food production, their vulnerability to sea level rise and flooding is a potential issue of national importance.

In addition to identifying and monitoring these hot spot areas, it may be worth reviewing whether current Environment Agency flood appraisal practices could better incorporate such concerns.

Conclusion

This analysis does not cover other problems with flood insurance, namely: the fact that despite the existence of Flood Re some people who should be eligible still find it a challenge to obtain insurance [xviii]; low insurance uptake amongst renters [xix]; lack of business insurance cover already starting to have localised economic impacts [xx]; and, householders being unwittingly caught out by cheap household insurance with no flood component [xxi]. Instead, it focusses on a specific part of the problem.

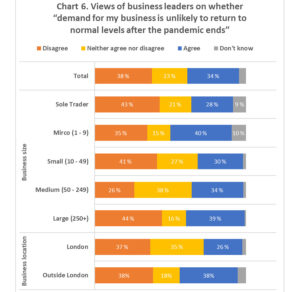

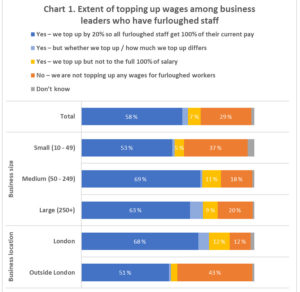

Base: 297 UK business leaders. Results for sole trader and micro business sizes are not shown due to small subsample size.

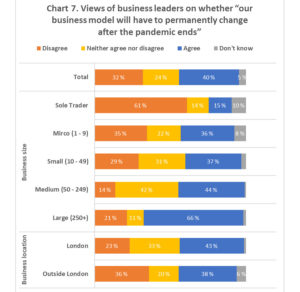

Base: 297 UK business leaders. Results for sole trader and micro business sizes are not shown due to small subsample size.