It is no secret that the economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic is worsening existing inequalities. The pandemic has had an asymmetric impact on jobs, putting the greatest strain on areas where sectors such as hospitality and tourism are significant, and which are more likely to employ low-income workers.

By examining differences in Universal Credit (UC) uptake across England, we can observe the severity of the pandemic’s economic impact on each local authority in England. We can explore the consequences of the pandemic on geographic inequality, specifically the Government’s ‘levelling up’ agenda which is trying to better support so-called ‘left-behind’ areas in coastal towns and industrial communities.

This analysis is unique in two ways. First, it is analysis which uses the latest available data on UC claimants, which is from October 2020. Second, this analysis goes beyond examining only increases in unemployment by English local authorities, by looking at overall increases in UC claimants, meaning we will capture both those who have become unemployed but also those still in work who have lost hours or income and now need to claim UC. It is important to consider the latter group, as while 56% of the increase in UC claimants between March and October 2020 is composed of unemployed claimants, 44% of this increase is composed of employed UC claimants.

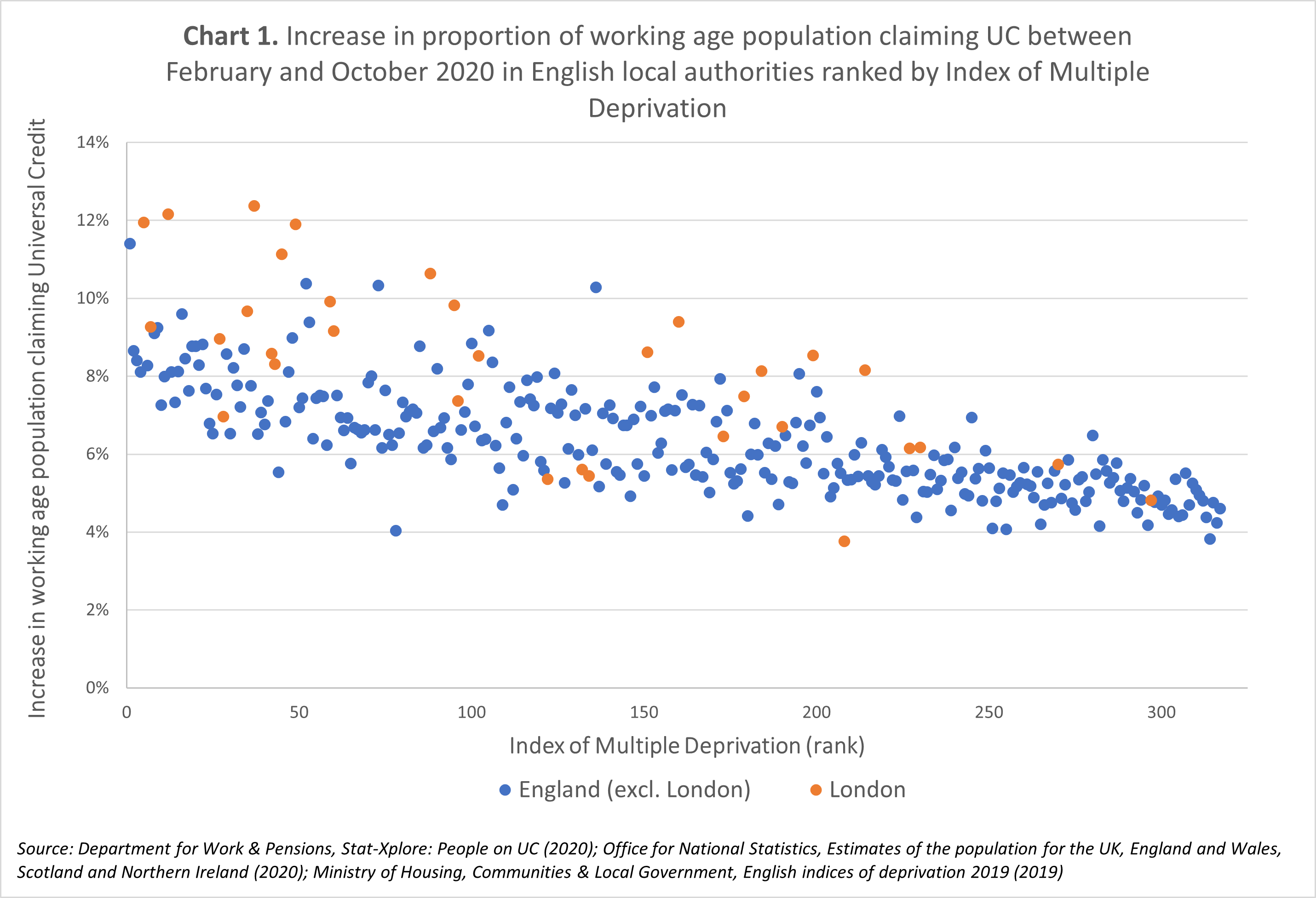

We first focus on the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) calculated in 2019, which aggregates deprivation factors related to income, employment, education, health, crime, barriers to housing and living environment. IMD ranks all local authorities, with a higher rank representing a higher degree of deprivation relative to other areas.[i] Hence, rank 1 represents the most deprived local authority and rank 317 the least deprived. We then compare it against the increases in the working-age population (those aged between 16 and 64) who are claiming UC between February and October 2020.[ii] [iii] As mentioned above, this increase in UC claimants not only includes individuals who have become unemployed during the pandemic, but also those in work who have started claiming UC due to a fall in their income.

The relationship between a local authority’s IMD ranking and increase in UC claimants during the first eight months of the pandemic is shown in Chart 1 below.

Chart 1 above illustrates the clear asymmetric nature of the pandemic’s impact, with local authorities that already faced higher deprivation also being more likely to see larger increases in proportion of people claiming UC. In fact, the 10% most deprived local authorities have seen on average an 8.5%-point increase in working age population claiming UC, as opposed to an average 4.8%-point increase for the 10% least deprived local authorities. Hence, the difference in increased uptake of UC is to some extent widening existing geographic inequalities. The pandemic is undermining the current Government’s attempt to ‘level up’ so-called ‘left-behind’ areas of the UK.

London local authorities, highlighted in orange, stand out as particularly unique. Generally, London local authorities have a much higher increase than non-London English local authorities in the number of UC claimants during the first eight months of the pandemic. This is unsurprising, considering many Londoners work in industries that have been affected the most by the pandemic. On average, London boroughs have seen an 8.3%-point increase in the working age population claiming UC as opposed to 6.3%-point increase in all other English local authorities.

But note among London local authorities the consistency with the trend among all other English local authorities: namely, more deprived London local authorities are more likely to have had a significant increase in UC claimants than the least deprived. In fact, for London local authorities, the disparities are even starker: the 10% most deprived London local authorities have seen an average 12.2%-point increase in UC claimants since February, in contrast to an average 4.6%-point increase in the 10% least London deprived local authorities.

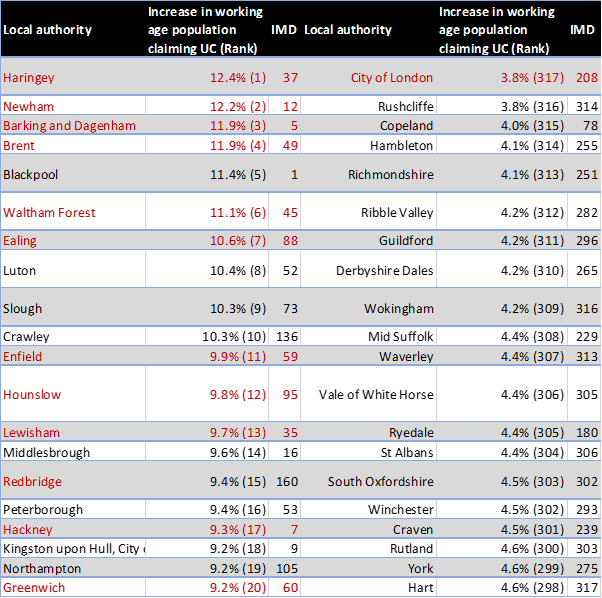

We can also rank the English local authorities with the highest and lowest increases in UC during the first eight months of the pandemic. Table 1 below shows the 20 local authorities in England with the highest and lowest increases in UC during the pandemic, alongside their IMD ranking.

Table 1. 20 English local authorities with the highest (left) and lowest (right) increase in proportion of working age population claiming UC between February and October 2020

Source: Department for Work & Pensions, Stat-Xplore: People on UC (2020); Office for National Statistics, Estimates of the population for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland (2020); Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government, English indices of deprivation 2019 (2019)

As shown in red in Table 1, London local authorities dominate the top 20 local authorities with the biggest increase in UC claimants in the first eight months of the pandemic. Specifically, 12 of the 20 local authorities with the highest increases in UC claimants were in London.

The London borough of Haringey has seen the biggest increase in UC claimants since February, of 12.4%-points, meaning that in October, 19.7% of its working age population were claiming UC.

Table 1 also shows that, other than the unique borough of the City of London, the local authorities that have experienced the lowest increase in UC claimants are outside London and have very low deprivation. Alongside the City of London, Rushcliffe, an affluent district in Nottinghamshire, has seen the smallest increase – of 3.8%-points. This means only 6.2% and 6.7% of the working age population in the City of London and Rushcliffe respectively are currently claiming UC.

Many of the places that have seen the greatest increases in UC claimants outside of London are English local authorities which have already struggled significantly economically and socially. Some of the local authorities with the highest increases, such as Blackpool (the most deprived local authority in England, according to the IMD), Hull and Middlesbrough, are coastal towns and post-industrial communities, prime targets for the ‘levelling up’ agenda of the current Government.

As unemployment continues to rise, and job hours and opportunities reduced, it will be essential for government to help people find new jobs or more hours quickly so they do not suffer the scarring impacts of long-term unemployment or underemployment, providing appropriate education and training support for those who would benefit from it.

But some local authorities will be better able to bounce back and increase employment opportunities. This is because there is a strong correlation between those with higher educational attainment and a shorter period of time spent in unemployment.[iv]

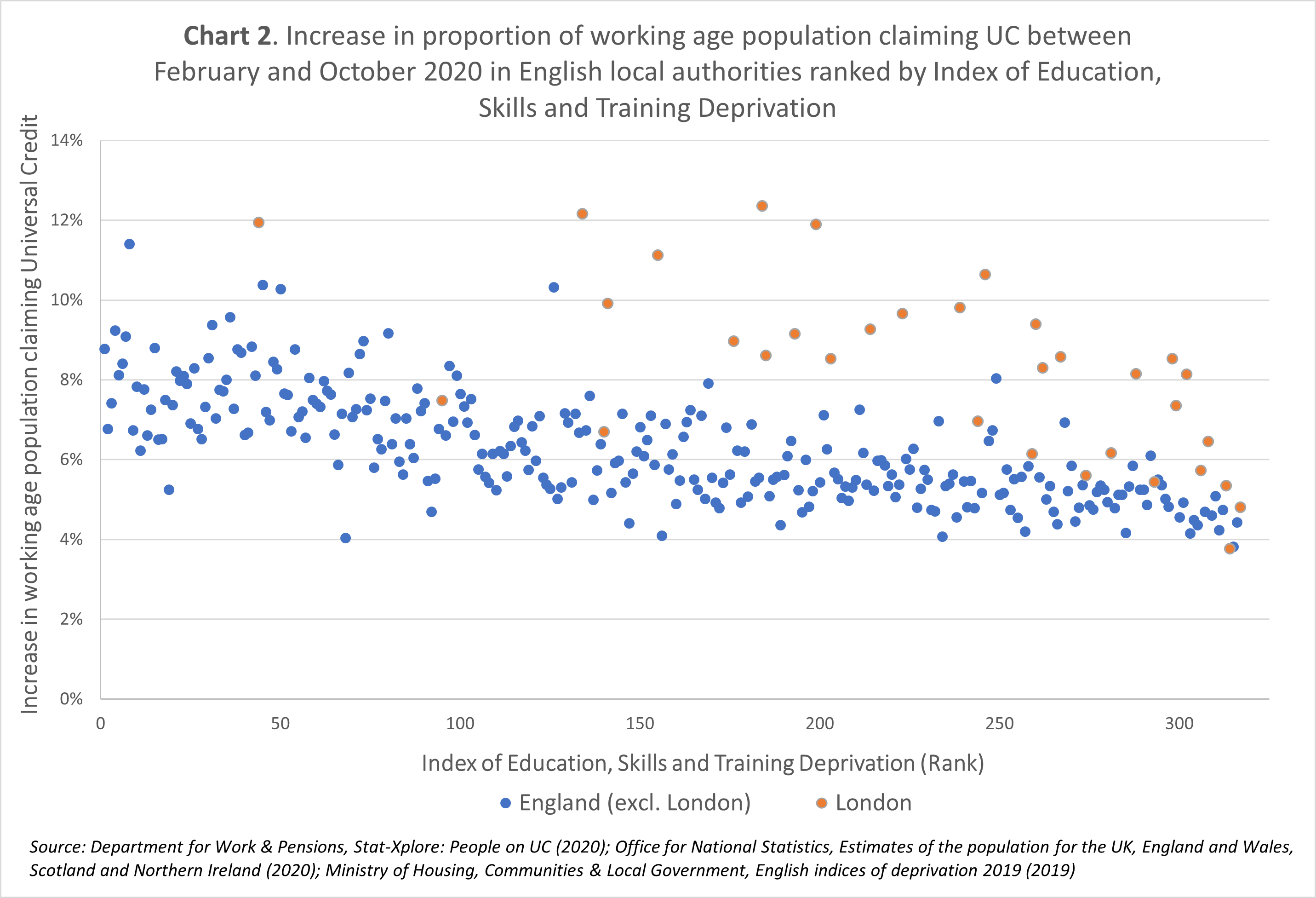

We now focus on the Index of Education, Skills and Training Deprivation, calculated in 2019, which ranks local authorities on a combination of rates of school attainment, school absences, entry to higher education, number of adults with low qualifications and English language proficiency.[v] A higher rank represents a higher degree of deprivation relative to other local authorities, meaning rank 1 represents the most educationally deprived local authority and rank 317 the least deprived. We then compare it against the increases in the working-age population (those aged between 16 and 64) who are claiming UC between February and October 2020.

Doing this analysis will indicate whether the geographical inequalities caused by the pandemic are likely to be sustained for a longer time. In other words, if local authorities have high rates of UC claimants but high education levels, they may be able to bounce quicker in terms of employment outcomes, whereas local authorities with high rates of UC claimants but low education levels, may struggle and be left-behind even more for a longer period of time.

The relationship between a local authority’s Index of Education, Skills and Training Deprivation ranking and increase in UC claimants during the first eight months of the pandemic is shown in Chart 2 below.

Chart 2 illustrates a clear relationship between local authorities experiencing higher rates of UC claimants and having lower levels of education, according to the Index of Education, Skills and Training Deprivation. The gap is notable, with the 10% most educationally deprived local authorities seeing an average 7.7%-point increase in working age population claiming UC, as opposed to a 5.3%-point increase in the 10% least educationally deprived. This indicates that those English local authorities experiencing higher rates of UC claimants are also those less likely to be able to bounce back quickly with increased employment outcomes. This implies the pandemic could be undermining government attempts to ‘level-up’ so-called left-behind areas of the country over the long-term.

Chart 2 illustrates a clear relationship between local authorities experiencing higher rates of UC claimants and having lower levels of education, according to the Index of Education, Skills and Training Deprivation. The gap is notable, with the 10% most educationally deprived local authorities seeing an average 7.7%-point increase in working age population claiming UC, as opposed to a 5.3%-point increase in the 10% least educationally deprived. This indicates that those English local authorities experiencing higher rates of UC claimants are also those less likely to be able to bounce back quickly with increased employment outcomes. This implies the pandemic could be undermining government attempts to ‘level-up’ so-called left-behind areas of the country over the long-term.

As Chart 2 shows, London is unique again, in that its local authorities have high increases in UC claimants but relatively high education levels. This means it is better placed to revitalise levels of employment outcomes quickly, since its population has relatively higher levels of education and skills. In the long-term, then, despite the generally higher increases in UC claimants in London now, it could be that more deprived areas of England outside London – especially in industrial and coastal communities – experience more long-term reduced employment opportunities.

But note among London local authorities the consistency with the trend among all other English local authorities: namely, more educationally deprived local London authorities are more likely to have had a significant increase in UC claimants than the educationally least deprived, with the 10% most educationally deprived areas in London seeing an average 10.5%-point increase in UC claimants as opposed to an average 4.6%-point increase for the 10% least educationally deprived.

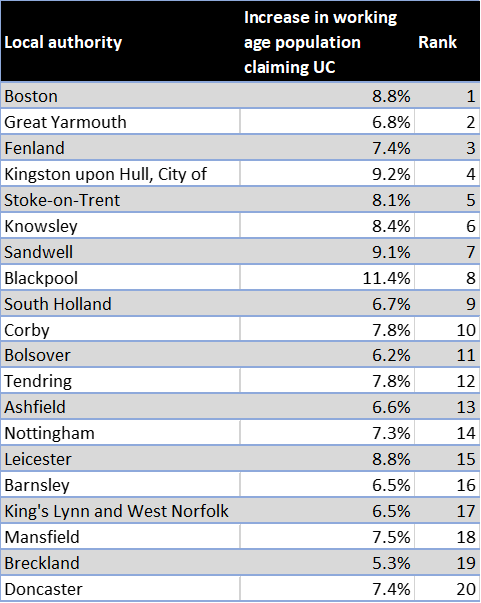

Table 2 lists the top 20 most educationally deprived local authorities in England alongside the increase in UC claimants for the first eight months of the pandemic.

Table 2. 20 English local authorities with the lowest rank of Education, Skills and Training deprivation and the increase in proportion of working age population claiming UC between February and October 2020

Source: Department for Work & Pensions, Stat-Xplore: People on UC (2020); Office for National Statistics, Estimates of the population for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland (2020); Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government, English indices of deprivation 2019 (2019)*Local authorities in London are marked in red

Table 2 shows that the most educationally deprived local authorities in England are in so-called left-behind areas, industrial and coastal communities such as Boston, Hull, Stoke-on-Trent, Blackpool, and Bolsover. In fact, eight of these 20 English local authorities are in at least one constituency which belonged to the so-called Red Wall seats that the Tories won in the 2017 or the 2019 General Election, making them a key part of the Conservative Party’s future electoral success.

These so-called left-behind areas already required significant support and investment before the pandemic. The pandemic risks causing them to fall further behind, especially in regards to employment opportunities. The pandemic really has made ‘levelling up’ a lot harder. The Government should ensure that these areas get sufficient resources when the pandemic ends, and the economic recovery begins, to avoid this.

Anvar Sarygulov is a Senior Research Fellow at Bright Blue.

Endnotes

[i] Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government, “English indices of deprivation 2019”, https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2019 (2019).

[ii] Office for National Statistics, “Estimates of the population for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland”, https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/populationestimatesforukenglandandwalesscotlandandnorthernireland (2020).

[iii] Department for Work and Pensions, “People on Universal Credit”, Stat-Xplore, https://stat-xplore.dwp.gov.uk/webapi/jsf/login.xhtml (2020).

[iv] W.C. Riddell and X. Song, “The Impact of Education on Unemployment Incidence and Re-employment Success: Evidence from the U.S. Labour Market”, Institute for the Study of Labour, http://ftp.iza.org/dp5572.pdf (2011).

[v] Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government, “English indices of deprivation 2019”, https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2019 (2019).